Rick Baker is closing up shop. The legendary special-effects and makeup creator recently announced that he would be shuttering his studio and auctioning off 400 of his best-known props. Baker’s career included some of the most enduring effects imagery of the 20th century, including work on The Exorcist, Star Wars, the “Thriller” music video, and Men in Black. For 35 years, his iconic costumes, makeup, and props defined film effects just prior to our own age of computer-generated imagery. The auction marked a bittersweet moment in film history; the end of an era—if not precisely the era of practical effects, then at least the era of Rick Baker’s work in film.

By chance, the auction took place on opening day for San Andreas, a CGI-fueled disaster blockbuster. In its review of San Andreas, the New York Times noted the obvious: “the most disturbing thing about this may be how dull and routine it seems. Computer-generated imagery can produce remarkably detailed vistas of disaster… but the technology also has a way of stripping such spectacles of impact and interest.” The contrast with old-fashioned practical effects was stark. In An American Werewolf In London, Baker showed a man transforming into a wolf onscreen, something that had previously only been hinted at with dissolves and cutaways. The effect had astonished audiences. Now the ability to amaze seemed itself doomed for extinction.

I met up with Baker in a colossal conference room at the Universal City Hilton. At 64, he is trim, gracious, and conspicuously enthusiastic—the kind of guy most men would like to age into as they approach retirement. We were given a few minutes to chat before the sale got underway.

ICE: I heard you on NPR the other day, and I was struck by your lack of bitterness. On one hand, you were saying that CGI had played a large role in the closing of your studio, and on the other hand you were saying you were comfortable with that.

Rick Baker: It wasn’t just CGI. I’ve seen that come up a lot. Ever since that NPR thing, I’ve been getting a lot of tweets saying, “End of an era, end of an era.” You know, it’s kind of been that for a while. The whole business has changed. I had a 60,000-square-foot studio, which was great for How the Grinch Stole Christmas and Planet of the Apes.But it’s not great for making a nose for somebody. And I’ve had that. I had one project where I had a guy making some teeth, in this 60,000-square-foot building, by himself, in summer. My air conditioning bill was more than I was getting paid to make the teeth. So it just became time. Those big jobs don’t exist anymore. As a young man, when I finally started meeting some people in the industry, I met a lot of bitter people, and a lot of crabby old guys, and I thought, How can you be like that? You’re in this amazing industry doing these cool things. And I didn’t want to become that.

Much of your work involves faces. Which seems ironic, because faces are the hardest things to fake with CGI. Avatar got it right, and then Tron: Legacy got it wrong a year later. Do you think there will be work for practical effects and makeup people doing facial design for CGI films?

Yeah, I do think so. When CG first became popular, we instantly became dinosaurs. But what happened was [the studios] started coming around, realizing that we actually had a skill set. I was brought in to do some damage control on The Curious Case of Benjamin Button. I said I would do it, but I didn’t really want credit, because they wanted to do this CG head. They said, “You can model this stuff in the real world better than we can on the computer.” So we actually modeled and made real, completely finished, silicone heads that they scanned to make their computer model from.

I was always hoping for a much closer marriage between the CG and the makeup stuff. I’ve been designing on a computer since the late 80s—’89, I think—because I saw the writing on the wall, too. I’ve been doing computer models, and doing my designs extensively on a computer, and I love it. I love doing digital models and digital paintings, and playing with digital compositing. But I don’t think it’s the answer to everything. I think you’re going to lose something.

When you have a good actor, in a good makeup, and he’s been sitting in the makeup chair looking at himself in the mirror, seeing himself become something else, and then he walks onto a set and he knows where he is, he knows what he looks like, he gives a performance that he’s never going to give on a motion-capture stage.

Now that CGI can show nearly anything, do you think filmmakers have lost the ability to astonish audiences? I’m thinking of that transformation scene inAmerican Werewolf… Is that kind of jolt just not possible any more?

Well, there seems to be a lot of CGI backlash, and [talk that] they’re going to bring back practical effects. But it’s not happening that much. I loved Mad Max: Fury Road, [seeing] a 70-year-old director kicking every young punk’s ass. And the fact that there was so much practical stuff. It does give you a different kind of adrenaline rush. I have the hardest time going to movies now and caring about stuff. I’m an effects nerd, that’s the kind of stuff that got me into this, and I watch films and I’m like, Why do I not care?Why am I just so bored? That’s one of the downfalls of the CGI stuff. You can do anything. But does it make it better? I don’t necessarily think so. But yeah, I think there’s a real difference when you know that something’s really happening. That guy really did risk his life, and this guy’s really standing in front of the camera doing this. I would rather watch an old Ray Harryhausen movie and suffer through 45 minutes of bad dialogue to get the 30-second stop-motion shot.

Looking through the auction catalogue, I was horrified by the “loose Edgar skins” from Men in Black. They’re terrifying. In your huge 60,000-square-foot studio, you must have had a lot of faces with empty eyes staring at you. Did that get creepy?

I grew up in a bedroom full of that stuff, from the time I was ten. It doesn’t scare me.

There’s never a point when you’re walking to the bathroom, late at night, and you bump into something soft and eyeless…

When it’s something that’s come out of your head, and made your hands, it’s not frightening. But if a film is well made, I can still be affected by it. I remember working onThe Exorcist, when I was in my early 20s, with the master, Dick Smith. I did the majority of the work on the head—the body and the head—when her head turns around, so I knew that very well. But when I saw the film, I found it as frightening as everybody else. And I was impressed by that. That’s filmmaking. It’s so hard to see a film that you worked on and be affected by it.

Michael Jackson contacted you for work on the “Thriller” video—is that correct?

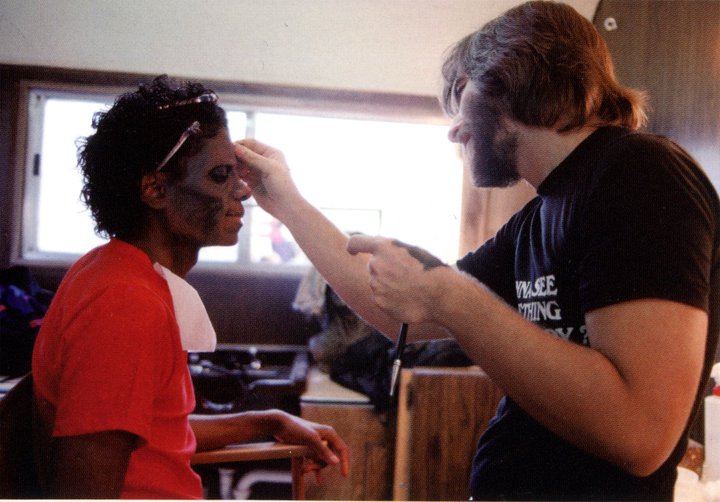

He contacted John Landis because of An American Werewolf in London. I was the first phone call that John made, and he said, “Michael Jackson wants to do a rock video… very much American Werewolf–influenced. He wants to transform.” I said, “Little Michael Jackson?” and he was like, “Well, he’s not little Michael Jackson anymore.”

I was really concerned about making up a pop star. I thought, This is going to be difficult, and he’s not going to be a good subject for this. But I was totally wrong. He loved it, [but] it was chaotic, and I had a whole lot of work to do in a very little amount of time. I had to use union makeup artists whom I didn’t really know, and didn’t know what they could do to apply these makeups on the dancers, and I was applying makeup on Michael on the same night, running around the makeup trailers, going, “No, no, no…” And there we were, in Vernon, the meatpacking district, in the middle of the night, and they started doing the “Thriller” dance…

Vernon must’ve had no one there at that point. You were probably the only audience.

Yeah. The worst part was, we started filming right around the time they start slaughtering animals. They do it at like two in the morning, and there was, like, a smell. It was literally right outside of the slaughterhouse. That was a little bit creepy. So I was standing there in the middle of the street, watching what was happening in front of my eyes, and my brain did a complete 360, and it was like, “Look at what’s happening in front of you, Rick.” Landis said to me, on that night, “People are going to know you more for this than for anything you do the rest of your career.” And it’s true. When people say, “What do you do for a living?” I say, “I’m a makeup artist.” “Have you done anything that I would have seen?” I say, “Yes,” and they say, “What?” I say, “‘Thriller,'” and it’s like, “You did ‘Thriller’?”

People are more impressed with that than your work on the cantina scene in Star Wars?

Yeah. “Thriller” is the one that I know people have seen. But yeah, it’s all about getting the work done, because you have so much to do in the preproduction, and you spend every waking hour working. Then when you’re on the set and you get the makeup on this actor, and you actually see it start to become this living, breathing thing, it’s magical.

Sounds like something you might miss.

I’m gonna miss a part of it. But I’m not gonna miss the chaos of the business. I didn’t get into this to become a businessman—I got into this to make things. And I’m still gonna make things. I’m making things every day, and they get to be what I want to make.

Baker’s presence was requested. I took a seat in the last row of the cavernous Ballroom C, not far from a display table of aliens and severed heads, a fraction of the collection up for sale. In the distance, a stage had been decorated with a full-sized Men in Black alien, the eponymous Grinch, a seemingly ancient gargoyle, and a decayed corpse tied to a chair with its throat slit. A man in a suit jacket welcomed the meager crowd—most bidding was done online or by phone—with a plea to take our auction paddles and “wave ’em like you just don’t care.”

I badgered a Hilton employee for the ballroom’s dimensions and did some quick math. Baker’s studio was 15 times the size of the massive conference room. I tried to imagine such a space, its parade of aliens and apes and monsters stretching to the horizon. I couldn’t quite picture it. Far away, the auctioneer banged his gavel. One sale down, 399 to go. It was going to be a long auction.

SOURCE: VICE