SAN RAFAEL, Calif. — Michael Jackson came back to life last Sunday on the Billboard Music Awards telecast. And the team that orchestrated his high-tech resurrection is beaming through their fatigue.

“It scared us to death to create an image that had to look, feel and function for four minutes like an entertainer everyone in the world knows,” says Frank Patterson, CEO of digital effects firm Pulse Evolution. “You have to see his eyes and moves and believe it was him.”

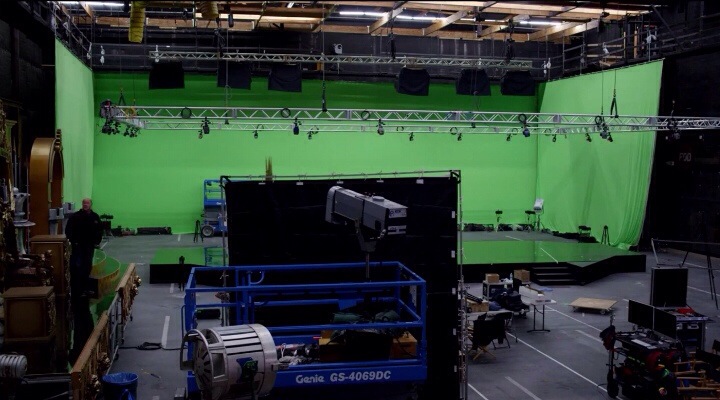

After a week of social and online media speculation about how the effect was pulled off, Florida-based Pulse exclusively invited USA TODAY to its Bay Area studios, located in the former headquarters of George Lucas’ Industrial Light & Magic, to explain the details behind Jackson’s performance of Slave to the Rhythm, off the late singer’s new album, Xscape.

But first, a plea. “It’s not a hologram,” says Pulse Executive Chairman John Textor, sitting in the room where the Jackson effect was crafted with Patterson and visual effects supervisor Stephen Rosenbaum, who worked on Avatar.

So what is it? “An illusion,” Patterson says.

Indeed, Pulse refined a 19th-century magician’s technique called Pepper’s ghost, which Textor — then leading Oscar-winning graphics company Digital Domain — also employed to summon the ghost of slain rapper Tupac Shakur at the Coachella music festival in 2012. The effect involves projecting an image on glass or plastic at a 45-degree angle, which brings that image into the viewer’s field of view.

But the Jackson illusion was infinitely more complex to pull off. “Tupac had no hair, and just stood there, where Michael had to be all over the place,” Patterson says.

Pulse Executive Chairman John Textor, left, and CEO Frank Patterson discuss the creation of the Michael Jackson illusion at the Pulse studio in San Rafael, Calif., on May 21, 2014.(Photo: Martin E. Klimek ,USA TODAY)

Here’s how things went down over eight long months of development.

Pulse first recorded Slave‘s gilded backdrop and real dancers in staggering 8K resolution (4K TVs are state of the art), using two $50,000 Red Dragon cameras. Next, a computer-generated Jackson circa 1991 (the period chosen by the Jackson estate) was subjected to an arduous animation process that was crucial to its success.

“You have to get across what’s called the ‘uncanny valley,’ which says the closer you get to making a digital human real, the creepier it gets,” says Patterson, adding that the illusion still lacked believability two weeks before the awards. “In the end, with all the intricate details in Michael’s face and gestures, we feel we got across.”

Come showtime, Pulse hung six high-powered projectors overhead and aimed the high-resolution footage of Jackson dancing and singing down at a piece of Mylar.

To the audience assembled at Las Vegas’ MGM Grand, it looked as if a life-size Jackson was in front of them. The illusion was cemented by the presence of live dancers (foreground) and band (background).

“When the people who knew Michael best started crying at the show, we knew we’d done something,” Textor says. “Then we started crying.”