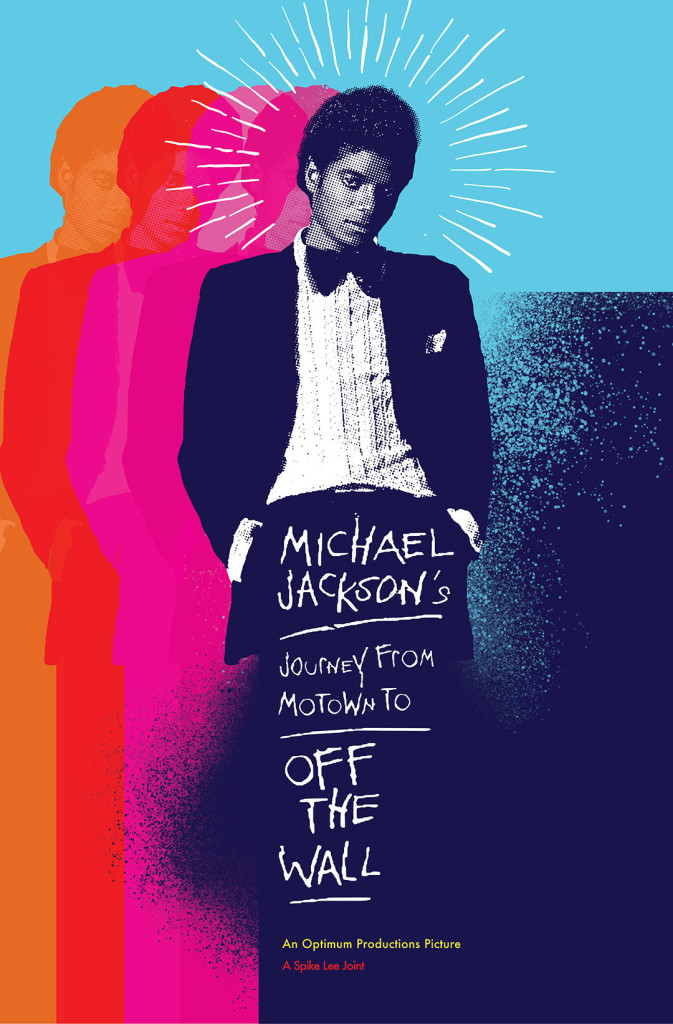

Spike Lee contextualizes the landmark 1979 album that cemented Jackson’s status as a superstar solo artist and propelled him on to an even bigger breakthrough with ‘Thriller.’

The first bars of “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough” are among the most iconic sounds in 20th century pop — that teasing entry beat, those half-whispered Stars Wars-esque opening lyrics (“The force, it’s got a lot of power”) and that signature falsetto “Woooh!” that uncorks a whole mess of infectious funk from the horns and percussion. Spike Lee takes us back to the first time we heard that classic in Michael Jackson’s Journey From Motown to Off the Wall, which continues the director’s admirable bid to reclaim the legacy of an innovative artist whose genius was often unfairly overshadowed in his later years by tabloid attention.

Following its Sundance premiere, the documentary begins airing Feb. 5 on Showtime, and no doubt will be devoured by fans who grew up on Motown, and on the decade of artistic apotheosis that followed Jackson’s departure to CBS Records. It’s also an equally entertaining companion piece to Bad 25, Lee’s 2012 film that marked the quarter-century anniversary of Jackson’s album of that name.

Lee’s interest in Jackson goes beyond an appreciation of his music to acknowledge what an important figure the performer remains in black culture, bridging the divide that continued to separate many black artists from mainstream acceptance. It’s startling to be reminded that the music business was still tacitly segregated at that time, and despite Off the Wall selling six million copies in its first year alone, Jackson’s awards recognition was confined to the black R&B categories.

The director’s access is impressive. He talks to fellow artists, producers, songwriters, engineers and arrangers, as well as select Jackson family members (both parents, two brothers) and Motown godfather Berry Gordy. Throughout, there are illuminating insights into how a great pop song is built. There’s notably incisive commentary from Questlove, Mark Ronson and Philadelphia hitmakers Kenny Gamble and Leon Huff, while a number of contemporary artists acknowledge their deep debt to Jackson. Pharrell Williams says, “My music would not be here without that record,” while The Weeknd confesses, “I found my falsetto because of Off the Wall.”

Others weigh in strictly on a personal level, about indelible memories of Jackson’s music as the soundtrack to their youth, though some of this rhapsodizing becomes a touch repetitive. (A little of Lee Daniels’ preening goes a long way, for instance.)

The main body of the doc is a track-by-track analysis of each song on the album, skimming over minor entries like the drippy Paul McCartney cover, “Girlfriend,” to spend more time on the many standouts. Those include the three tracks written by Jackson — “Don’t Stop,” “Working Day and Night” and “Get on the Floor” — and Rod Temperton’s contributions, “Rock With You” and the title song. Those up-tempo hits prompt Ronson to describe the record as “a DJ’s dream.”

As for the slower grooves, Stevie Wonder discusses Jackson’s move into the quiet storm “boudoir demographic” with his song “I Can’t Help It.” And songwriter Tom Bahler applauds the sincere emotion Jackson poured into “She’s Out of My Life,” which segues hilariously into Eddie Murphy’s classic riff on Michael’s sensitivity: “Tito, get me some tissues.”

But what makes all this so absorbing is Lee’s meticulous attention to context. Starting with a vintage interview in which Jackson shares how the brothers began singing together just to goof off when the TV broke down, he recaps the early years with some fabulous archive material. (Those outfits!) It’s strangely touching to see Jackson with his natural skin color and pre-surgery features, a poignant reminder of the deteriorating grip on reality that defined his later years.

Lee declines to dig into the more controversial aspects of his subject’s upbringing, ignoring questions surrounding the extent to which Joe Jackson pushed his children to succeed professionally. Instead, he focuses on Michael’s singular drive and ambition, declaring early on that he was not going to be poor. Gordy and others talk about the adolescent Jackson’s tireless curiosity, watching and learning about every aspect of the craft from senior artists in the Motown family. By his own definition and that of others, Jackson became a perfectionist.

Perhaps the closest Lee gets to family friction is in allowing Jackson to speak for himself in a 1980 interview, excerpted near the end of the film, where he says he feels no guilt about leaving his brothers behind when he went solo. He makes no apologies for the fact that his creative hunger compelled him to move forward alone, and certainly no one can dispute that his artistry and talent far eclipsed that of the group.

The film pinpoints Jackson’s performance of “Ben” on the 1973 Oscars telecast as the first time he stepped out on his own. The exit from Motown to CBS subsidiary Epic Records in 1975 is depicted as a wrenching but necessary separation, with Walter Yetnikoff admitting that he was just three weeks into the job as president at the time and wanted to pass on the deal, until the A&R guys twisted his arm.

The Jacksons, as they then became known when Gordy refused to let go of the ‘Jackson 5’ name, were still struggling to shake off the cutesy image of their cartoon series. But Gamble and Huff produced two transitional albums that helped them hone a more adult sound. That shift is superbly illustrated in a stupendous American Bandstand clip of the Jacksons doing “Shake Your Body (Down to the Ground),” wearing powder-blue satin jumpsuits.

That clip also shows the development of Michael’s distinctive dance language, elements of which Lee traces to the Nicholas Brothers, James Brown, Jackie Wilson and Fred Astaire. Archival interviews with Sammy Davis Jr. and Gene Kelly reveal that they were flattered to observe traces of their dance styles in Jackson’s moves. Misty Copeland speaks about his amazing footwork, while Kobe Bryant admits that watching Jackson dance influenced his court moves.

A key stepping stone to Off the Wall was Jackson’s appearance in Sidney Lumet’s 1978 film of The Wiz, which despite its critical hammering, was a huge event for black America. (Who remembered that the very white Joel Schumacher back then was Hollywood’s go-to guy for black screenplays, writing Sparkle, Car Wash and The Wiz? Even he still seems surprised.) Appearing alongside an uncomfortably miscast Diana Ross, Jackson’s unique energy and spring-loaded physicality made his numbers bright spots in a very patchy movie.

More important, the film connected Jackson with his most essential collaborator, Quincy Jones. While the jazz maestro was an unconventional choice to produce a disco/funk/R&B album, his rhythmic sophistication helped Jackson shape his defining legacy, with the one-two-three smash succession of Off the Wall, Thriller and Bad, released over an eight-year period. Having surveyed the first and last of those albums, maybe Lee will next give us a comprehensive salute to the 1982 monster centerpiece? Here’s hoping.

Venue: Sundance Film Festival (Documentary Premieres)

Production company: Optimum Productions

Director: Spike Lee

Producers: Spike Lee, John Branca, John McClain

Director of photography: Kerwin DeVonish

Editors: Ryan Denmark, Barry Alexander Brown

Sales: ShowtimeNo rating, 93 minutes

This article originally appeared on THR.com.

SOURCE: Billboard